Ecommerce on Sinatra: A Shopping Cart Story

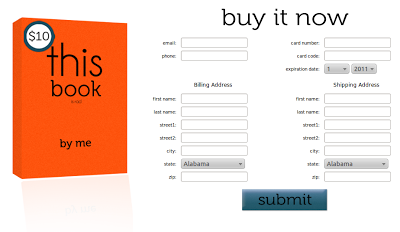

In a couple recent articles, I wrote about the first steps for developing an ecommerce site in Ruby on Sinatra. Or, here’s a visual summary of the articles:

|

|

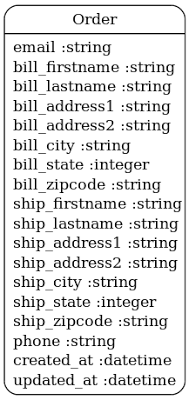

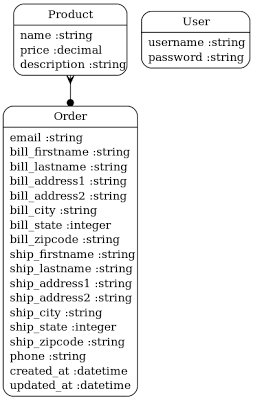

| In the first article, a single table data model existed with a couple of Sinatra methods defined. | In the second article, users and products were introduced to the data model. The Sinatra app still has minimal customer-facing routes (get "/", post "/") defined, but also introduces backend admin management to view orders and manage products. |

|

|

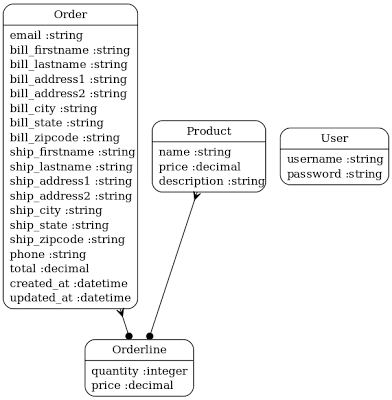

In this article, I introduce a shopping cart. With this change, I modify the data model to tie in orderlines, where orderlines has a belongs_to relationship with orders and products. I’ll make the assumption that for now, a cart is a set of items and their corresponding quantities.

The new data model with tables orderlines, products, orders, and users.

An Important Tangent

First, let’s discuss cart storage options, which is an important topic for an ecommerce system. Several cart storage methods are described below:

-

Conventional SQL database models: Conventional SQL (MySQL, PostgreSQL, etc.) tables can be set up to store shopping cart items, quantities, and additional information. This can be nice if designed so that cart information matches the existing data model (e.g. orders & orderlines), so data can be clean and easy to work with using object-relational mappers or direct SQL. For example this makes it easy for administrative tools to report on abandoned carts. One disadvantage of this kind of storage is that it increases database I/O at the already limited chokepoint of a master database. Another disadvantage is that you need to eventually clean up data as users abandon their carts, or deal with tables that grow large much more quickly than the orders tables. For example, Spree, an open source Ruby on Rails ecommerce platform that End Point works with frequently, stores carts in the database (order & line_items table), and for one of our clients, approximately 66% of the order data is from abandoned carts.

-

Serialized object store: Here cart items, quantities, and additional information is stored in a session object and serialized to disk in files, key/value stores like memcached, in NoSQL databases (some of which can scale horizontally fairly nicely), or even as a BLOB in an SQL database. Sessions are assigned a random ID string and linked to users either by a cookie or in the URL (note: tracking session IDs in URLs has become less common due to its interference with caching and search engine indexing). This type of storage is very convenient for developers and tends to perform fairly well. However, if there is heavy server load, saving the session at the end of every request can introduce a bottleneck, especially when multiple application servers are using a single shared session data store. Also, the developer convenience can turn into a mess if the session becomes a dumping ground for ephemeral data that becomes permanent, or which causes pages to be un-RESTful as they’re not based solely on the URL. Interchange, an open source Perl ecommerce framework that End Point works with often, uses this method of cart storage by default.

-

Cookie cart storage: Cart items, quantities, and additional information can be stored directly in cookies in the user’s browser. Cookies don’t add any server storage overhead, but do add network overhead to each request, and have limited storage space. Typically, you’d only want to store information in cookies that is fine in the untrusted environment of users’ browsers, such as SKU and quantity. You can introduce hashing to protect integrity if you want to include custom pricing, or reversible encryption of the data to store sensitive data, such as personalized product options or personal information.

-

JavaScript stored carts: An uncommon (but possible) cart-storage method is to store cart items, quantities, and additional information in a JavaScript data structure in the browser’s memory. This does not introduce any server-side load as storage and processing occurs on the client side. This could be done where front-end view manipulation occurs entirely by web service requests and JavaScript DOM manipulation: A user comes to the web store, products are rendered and listed with an AJAX request to the web service and a user manipulates the cart. All of this happens while the user never leaves the page. The cart object continues to reflect the user’s cart and is only sent to the server when the user is ready to finalize their order, along with billing, shipping, and other order information. This type of ecommerce solution isn’t SEO-friendly by default because it does not readily display all content, and closing the browser window for the store could lose the cart. But it might be suitable in some situations, and using new HTML 5 LocalStorage would add permanence and make this a more palatable option. End Point recently built a web service based YUI JavaScript application for Locate Express, but ecommerce is not a component of their system.

Back to the App

For this demo, I chose to go with Cookie-based cart storage for several reasons. At the lowest level, I define a few different structures for the cart:

- cookie_format: e.g. “2:1;18:2;”. semi-colon delimited items, where product id and quantity are separated by colon. This is the simplest cart format stored to the cookie.

- hash format: e.g: { 2: 1, 18: 2 }. keys are product ids, quantities are the corresponding hash values. This format makes the cart items easy to manipulate (update, remove, add) but does not require database lookup (potentially saving database bandwidth).

- object format: e.g.

>> @cart = Cart.new("2:1;18:2")

>> @cart.items.inspect

[

{ :product => #Product with id of 2,

:quantity => 1 },

{ :product => #Product with id of 18,

:quantity => 2 }

]

>> @cart.total = # sum of (item_cost*quantity)

The cart object is created whenever the cart and it’s items are displayed, such as on the actual cart page. Cart construction requires read requests from the database.

Next up, I define several Cart class methods for interacting with the cart:

def self.to_hash(cookie)

cookie ||= ''

cookie.split(';').inject({}) do |hash, item|

hash[item.split(':')[0]] = (item.split(':')[1]).to_i

hash

end

end

|

class method to convert cart from cookie format to hash |

def self.to_string(cart)

cookie = ''

cart.each do |k, v|

cookie += "#{k.to_s}:#{v.to_s};" if v.to_i > 0

end

cookie

end

|

class method to convert cart from hash format to cookie format |

def self.add(cookie, params) cart = to_hash(cookie) cart[params[:product_id]] ||= 0 cart[params[:product_id]] += params[:quantity].to_i to_string(cart) end |

class methods for adding, removing, and updating items. each method converts to hash then converts to hash format, performs operation, then returns as cookie format |

attr_accessor :items attr_accessor :total |

instance attributes (items, total) defined here and constructor pulls info from database and calculates the cart total upon initialization |

I define some Sinatra methods to work with my cart methods. I also update the order completion action to store orderline information:

app.get '/cart' do

@cart = Cart.new(request.cookies["cart"])

erb :cart,

:locals => {

:params => {

:order => {},

:credit_card => {}

}

}

end

|

Build our cart when a get request is made to "/cart". |

app.post '/cart/add' do

response.set_cookie("cart",

{ :value => Cart.add(request.cookies["cart"], params),

:path => '/'

})

redirect "/cart"

end

app.post '/cart/update' do

response.set_cookie("cart",

{ :value => Cart.update(request.cookies["cart"], params),

:path => '/'

})

redirect "/cart"

end

app.get '/cart/remove/:product_id' do |product_id|

response.set_cookie("cart",

{ :value => Cart.remove(request.cookies["cart"], product_id),

:path => '/'

})

redirect "/cart"

end

|

The post and get requests to add, update, and remove use the cart class methods. We set the request.cookie with a path of '/' and redirect to /cart. |

...

if order.save

cart = Cart.new(request.cookies["cart"])

cart.items.each do |item|

Orderline.create({ :order_id => order.id,

:product_id => item[:product].id,

:price => item[:product].price,

:quantity => item[:quantity] })

end

order.update_attribute(cart.total)

...

gateway_response = gateway.authorize(order.total*100, credit_card)

|

During order processing, orderlines are created and assigned to the current order and the payment gateway authorizes the order total. If a successful transaction goes through, the cart is set to an empty string. If not, the cart cookie is not modified. |

Conclusion

From the top: the changes described here introduce the orderlines table, a cart object and methods to manage items in the user’s cart and several Sinatra methods for working with the cart object. The homepage is updated to list items and add to cart form fields and the existing order processing method is updated to store data into the orderlines table.

Below are some screenshots from the resulting app with shopping cart functionality: the homepage, cart page, and the empty cart screenshot.

|

|

|

| homepage | empty cart display | shopping cart page |

The code described in this article is part of an ongoing Sinatra based ecommerce application available here. The repository has several branches corresponding to the previous articles and potential future articles. I’d like thank Jon for contributing to the section in this article regarding cart storage options.

Comments