String Processing in SQL, the Hard Way

Photo by Kristy Lee

Photo by Kristy Lee

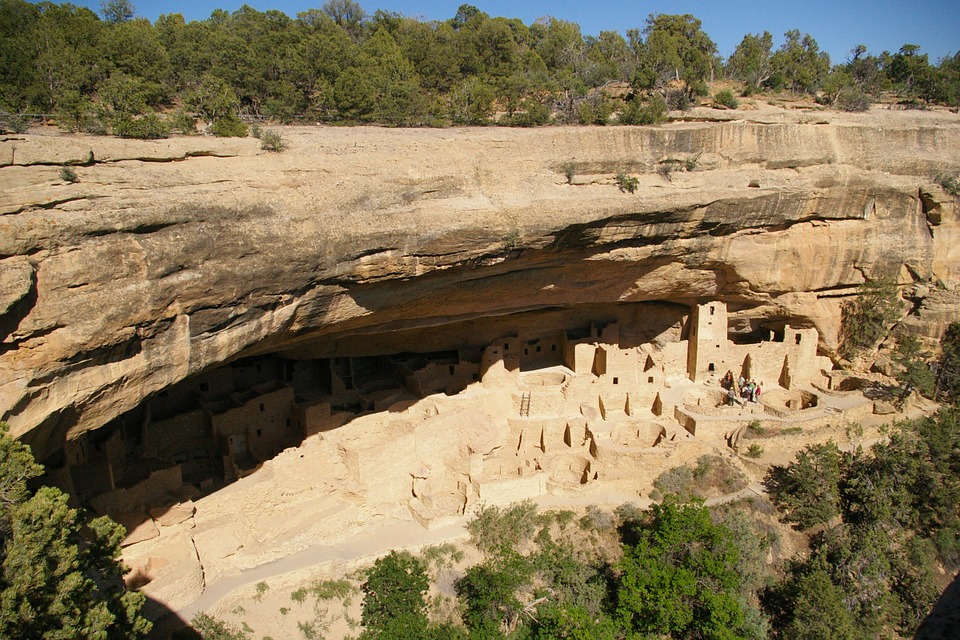

When I was a kid, my family visited a prehistoric cliff-dweller settlement, reconstructed and preserved as a museum exhibit. The homes were built in caves in high sandstone cliffs, and though I followed a well-marked path to visit them, the original inhabitants climbed in and out via holes cut into the rock face. Apparently to deter unwanted visitors, the builders carefully spaced the foot holds so that climbers needed to start their ascent on the correct foot. Someone who didn’t know the secret of the path, or who carelessly forgot, might get halfway up the cliff and discover he or she couldn’t stretch to the next foot hold and had to turn back.

The other day I found myself confronted with several comma-separated lists of strings, and a problem: I needed the longest possible substring from each, starting from the beginning, ending in a comma, and shorter than a certain length, and I needed to do it in the database. “Easy peasy,” you may say to yourself, if you have a little SQL programming experience and a penchant for cheesy clichés, and you’d be right except for one thing: I let my mind wander a little too far down into the uncharted mists of imagination and like the cliff dweller, I got off on the wrong foot. What followed was a thankfully brief exploration of the Hard Way to Do It.

The unsettling method on which I settled had me dividing each list into its component parts, reconstructing candidate results element by element, and finding the longest one less than the maximum overall length. Fortunately the problem didn’t allow me to reorder the elements in my input lists, or I’d probably still be working on this query. Here’s the monstrosity I eventually built:

select

length(c), c

from (

select

concat_ws(', ', variadic array_agg(f) over (rows between unbounded preceding and current row)) c

from (

select regexp_split_to_table('alpha, bravo, charlie, delta, echo, fox trot', ',\s+') as f

) f

) c

where length(c) < 30

order by length(c) desc nulls last

limit 1

The innermost subquery here, based on regexp_split_to_table, divides the input string into an ordered list of its component elements:

select regexp_split_to_table('alpha, bravo, charlie, delta, echo, fox trot', ',\s+');

regexp_split_to_table

-----------------------

alpha

bravo

charlie

delta

echo

fox trot

(6 rows)

I’m never one to bypass a good opportunity to shoehorn a window function into my SQL, and here we get to use the frame clause. Recall that for each row of a query, a window function processes a selection of rows, called a “partition”, and in fact processes only a “frame”, a subset of that partition. Window frames are fairly complicated subjects; I’ll try to present here a brief summary of the bits relevant to this query, and recommend the PostgreSQL documentation for further details.

Our particular window frame clause, rows between unbounded preceding and current row, means that the window frame for a given row should include all the rows from the first row of the partition through the current row. Given that we have no order by clause in our window definition, terms like “first row” refer to the first row in the order the rows were provided to the WindowAgg executor node. Whether it’s safe to trust that order to remain stable without a specific order by clause is an awfully good question I didn’t try to answer but for my purposes I needed to preserve the order of elements as returned by regexp_split_to_table. The default window frame clause is range unbounded preceding, which the documentation notes is a shortened form of range between unbounded preceding and current row, and without a specific order by clause, this means the window frame includes all rows in the partition. As a fun exercise, compare these two results, which differ only in the presence of an order by clause:

select array_agg(f) over () c

from (

select regexp_split_to_table('alpha, bravo, charlie, delta, echo, fox trot', ',\s+') as word

) f

;

c

-------------------------------------------------------------

{(alpha),(bravo),(charlie),(delta),(echo),"(\"fox trot\")"}

{(alpha),(bravo),(charlie),(delta),(echo),"(\"fox trot\")"}

{(alpha),(bravo),(charlie),(delta),(echo),"(\"fox trot\")"}

{(alpha),(bravo),(charlie),(delta),(echo),"(\"fox trot\")"}

{(alpha),(bravo),(charlie),(delta),(echo),"(\"fox trot\")"}

{(alpha),(bravo),(charlie),(delta),(echo),"(\"fox trot\")"}

(6 rows)

select array_agg(f) over (order by word) c

from (

select regexp_split_to_table('alpha, bravo, charlie, delta, echo, fox trot', ',\s+') as word

) f

;

c

-------------------------------------------------------------

{(alpha)}

{(alpha),(bravo)}

{(alpha),(bravo),(charlie)}

{(alpha),(bravo),(charlie),(delta)}

{(alpha),(bravo),(charlie),(delta),(echo)}

{(alpha),(bravo),(charlie),(delta),(echo),"(\"fox trot\")"}

(6 rows)

Anyway, that’s a tangent, but I found it a helpful one, as the default window frame is a well-known trap for young players, to which I’ve fallen prey in the past at least once. Back to my over-complicated query.

I’m aiming to produce a series of strings, each containing one more element than the last one. Now that I have a set of arrays with the elements I want inside, I turned to the concat_ws function to turn them into strings. concat_ws concatenates each of its arguments with a user-specified separator string, and the variadic keyword lets me pass an array of values and have them treated as individual arguments:

select

concat_ws(', ', variadic array_agg(f) over (rows between unbounded preceding and current row)) c

from (

select regexp_split_to_table('alpha, bravo, charlie, delta, echo, fox trot', ',\s+') as f

) f

;

c

----------------------------------------------

alpha

alpha, bravo

alpha, bravo, charlie

alpha, bravo, charlie, delta

alpha, bravo, charlie, delta, echo

alpha, bravo, charlie, delta, echo, fox trot

Now we’re getting close to the answer. My final steps are to filter out all resultant strings longer than the acceptable length and pick the longest one:

select

length(c), c

from (

select

concat_ws(', ', variadic array_agg(f) over (rows between unbounded preceding and current row)) c

from (

select regexp_split_to_table('alpha, bravo, charlie, delta, echo, fox trot', ',\s+') as f

) f

) c

where length(c) < 30

order by length(c) desc nulls last

limit 1

;

length | c

--------+------------------------------

28 | alpha, bravo, charlie, delta

(1 row)

Success! It only took about a hundred more steps than were really necessary. In my defense, it wasn’t too long after I’d finished composing this query that I realized I was making it much harder than I should have.

I posted it to our internal company chat, and within a minute or two my colleague Kürşat had answered with his own version:

SELECT regexp_matches(substring('alpha, bravo, charlie, delta, echo, fox trot' from 1 for 30), '(.*),');

regexp_matches

----------------------------------

{"alpha, bravo, charlie, delta"}

(1 row)

This simply finds a substring of acceptable length from the input text, and removes everything from the final comma onward. Not only did this take about 30 seconds to compose, compared to the half hour or so I’d spent on my first version, but on my laptop it completes in about half the time.

That fact notwithstanding, it’s often true that we learn rather a lot from our mistakes — and others’ mistakes — and I hope that’s true for you in this case.

Comments