Facial Recognition Using Amazon DeepLens: Counting Liquid Galaxy Interactions

I have been exploring the possible uses of a machine-learning-enabled camera for the Liquid Galaxy. The Amazon Web Services (AWS) DeepLens is a camera that can receive and transmit data over wifi, and that has computing hardware built in. Since its hardware enables it to use machine learning models, it can perform computer vision tasks in the field.

The Amazon DeepLens camera

This camera is the first of its kind—likely the first of many, given the ongoing rapid adoption of Internet of Things (IoT) devices and computer vision. It came to End Point’s attention as hardware that could potentially interface with and extend End Point’s immersive visualization platform, the Liquid Galaxy. We’ve thought of several ways computer vision could potentially work to enhance the platform, for example:

- Monitoring users’ reactions

- Counting unique visitors to the LG

- Counting the number of people using an LG at a given time

The first idea would depend on parsing facial expressions. Perhaps a certain moment in a user experience causes people to look confused, or particularly delighted—valuable insights. The second idea would generate data that could help us assess the platform’s impact, using a metric crucial to any potential clients whose goals involve engaging audiences. The third idea would create a simpler metric: the average number of people engaging with the system over a period of time. Nevertheless, this idea has a key advantage over the second: it doesn’t require distinguishing between people, which makes it a much more tractable project. This post focuses on the third idea.

To set up the camera, the user has to plug it into a power outlet and connect it to wifi. The camera will still work even with a slow network connection, though when the connection is slower the delay between the camera seeing something and reporting it is longer. However, this delay was hardly noticable on my home network which has slow-to-moderate speeds of about 17 Mbps down and 33 Mbps up.

Computer Vision and the Amazon DeepLens

A deep learning model is a neural network with multiple layers of processing units. It is called “deep” because it has multiple layers. The inputs and outputs of each processing unit are numbers. These units are roughly analogous to neurons: they receive input from units in the previous layer, and output it to units in the next layer after transforming it based on a function. These “activation functions” can change in a variety of ways. The last layer’s outputs translate into the results. These models work because these functions get tuned based on how well the model works. For example, to make a model that labels each human face in a picture and draws a box around it, we would start with a corpus of pictures with boxes drawn around faces, as well as the versions of the pictures without the boxes drawn. We would test the model on the non-labeled images by checking—for each picture—whether the output generated by the model is correct. If not, the computer chooses different unit functions, tries again, and compares the results. Repeating this process thousands of times yields models which work remarkably well for a wide range of tasks, including computer vision.

In deep learning for computer vision, training on large sets of labeled images enables models to generalize about visual characteristics. The training process takes a lot of computing resources, but once models are trained, they can produce results quickly and with relative ease. This is why the DeepLens is able to perform computer vision with its limited computing resources.

Since the DeepLens is an Amazon product, it comes as no surprise that the user interface and backend for DeepLens consist of AWS services. One of the most important is SageMaker, which is used to train, manage, optimize, and deploy machine learning models such as neural networks. It includes hosted Jupyter notebooks (Jupyter is a development environment for data science), as well as the computing resources required for model training and storage. With SageMaker, users can train computer vision models for deployment to DeepLens, or import and adjust pretrained models from various sources.

Remote management of the DeepLens depends on AWS Lambda, a “serverless” cloud service that provides an environment to run backend code and integrate with other cloud services. It runs the show, allowing users to manage everything from the camera’s behavior to what happens to gathered data. Another service, AWS Greengrass, connects the instructions from AWS Lambda to the DeepLens, managing tasks like authentication, updates, and reactions to local events.

Amazon’s IoT service saves information about each DeepLens, and allows users to manage their devices, for example by choosing which model is active on the device, or viewing a live stream from the camera. It also keeps track of what’s going on with the hardware, even when it’s off. When a model is running on the DeepLens, you can view a live stream of its inferences about what it’s seeing (the labeled images). Amazon has released various pretrained models designed to work on the DeepLens. Using a model for detecting faces, we can get a live stream that looks like this:

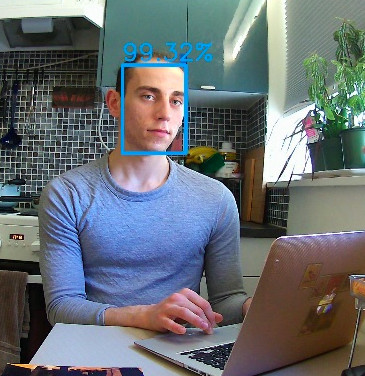

Me looking at the DeepLens in my kitchen

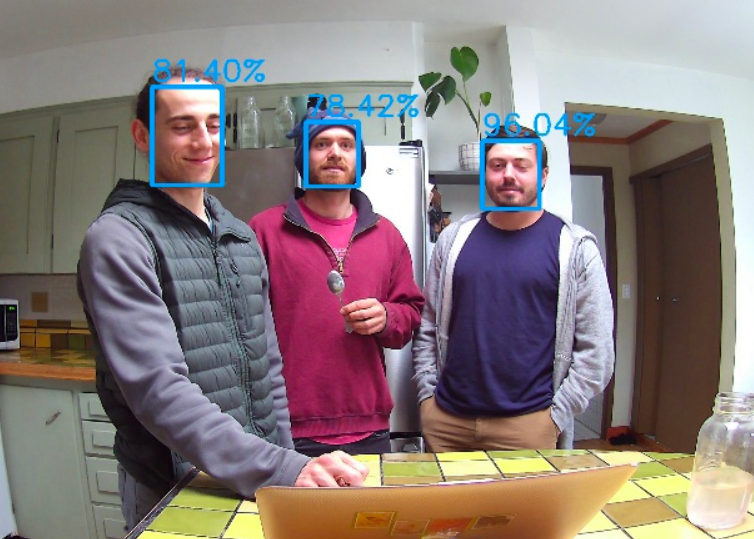

Facial recognition inferences on multiple people. (Witness my smile of satisfaction at finally finding enthusiastic subjects of facial recognition.)

Each face that the camera detects gets a box around it, along with the model’s level of certainty that it is a face. The above pictures were the results of an attempt to simulate the conditions where this could be used.

The Model

The model I used was trained on data from ImageNet, a public database with hundreds or thousands of images associated with nouns. (For example they have 1537 pictures of folding chairs.) ImageNet is commonly used to train and test computer vision models.

However, the training for this model didn’t stop there: Amazon used transfer learning from another large image dataset, MS-COCO, to fine-tune the model for face detection. Transfer learning works essentially by retraining the last layer of an already-trained model. In this way it harnesses the “insights” of the existing model (e.g. about shapes, colors, and positions) by repurposing this information to make predictions about something else. In this case, whether something is a face.

Since this model was pretrained and optimized by Amazon for the DeepLens, it provides a low effort route to implementing a computer vision model on the DeepLens. I didn’t have to do any of the processing on my own hardware. The DeepLens hardware took care of all the predictions, though the biggest resource savings were from not having to train the model myself (which can take days, or longer).

When the facial recognition model is deployed and the DeepLens is on, an AWS Lambda function written in Python repeatedly prompts the camera to get frames from the camera:

frame = awscam.getLastFrame()

…to resize the frames before inference (the model accepts frames of particular size):

frame_resize = cv2.resize(frame, (input_height, input_width))

…to pass the frames to the model:

parsed_inference_results = model.parseResult(model_type, model.doInference(frame_resize))

…and to use the results to draw boxes around the faces:

cv2.rectangle(frame, (xmin, ymin), (xmax, ymax), (255, 165, 20), 10)

As you can see from how often “cv2” appears in the code above, this implementation relies heavily on code from OpenCV, an open source computer vision framework. Finally, the results are sent to the cloud:

client.publish(topic=iot_topic, payload=json.dumps(cloud_output))

In the last code snippet above, iot_topic refers to an Amazon “MQTT topic” (Message Queuing Telemetry Transport), for IoT devices. MQTT is the standard connectivity framework for DeepLens and many other IoT devices. One of its advantages for this context is that it can handle situations with intermittent connectivity, by smoothly queueing messages for when the network connection is stable. The essence of MQTT is to enable publishing and subscribing to different topics. The system of topics enables results from a DeepLens to trigger other processes. For example, the DeepLens could publish a message when it sees a face, and this could prompt another cloud service to do something else, such as save what time and how long the face appeared.

I wanted to test how data from this model would compare to a human’s perception. The first step was to understand what data the camera offers. It produces data about each frame analyzed: a timestamp (in 13-digit Unix time), and the predicted probability that something it identifies is a face. To gather this data, I used the AWS IoT service to manually subscribe to a secure MQTT topic where the DeepLens published its predictions. Each frame processed produces data like this:

{

"format": "json",

"payload": {

"face": 0.5654296875

},

"qos": 0,

"timestamp": 1554853281975,

"topic": "$aws/things/deeplens_bnU5sr2sSD2ecW5YkfJZtw/infer"

}

The data generated by a single frame (with one face) when processed by the DeepLens.

For my purposes, I was only interested in the timestamps and payloads (which contain the number of faces identified, and their probabilities). I decided to test the facial recognition model under several different conditions:

- No faces present

- One face present

- Multiple faces present

For condition 1 I just aimed it at an empty room for 20 minutes, and for condition 2 I sat in front of the camera for 20 minutes. For condition 3, I aimed the camera at a public space for 20 minutes, and while it was running I kept an ongoing count of the number of people looking in the general direction of the camera (I put the camera in front of a wall with a TV on it so people would be more likely to look towards it). Then I averaged my count over the duration of the sample, which resulted in an average engagement number of 2.5 people, meaning that on average, 2.5 people were looking at the camera. In an attempt to minimize bias, I made my human-eye assessment before looking at any of the data.

I’ll spoil one aspect of the results right away: there were no false positives under any condition. Even the lower probability guesses corresponded to actual faces, though this result might not hold true in a room with lots of face-like art, that’s not too common of a scenario. This simplified things, since it meant there was no need to set a lower bound on the probabilities which we should count—any face detected by the camera is a face. This also highlights one of my remaining questions about the model: is there useful information to be gained from the probabilities?

Another important note: I noticed early in the experiment that it almost never detects a face farther than 15 feet away. For the use case of a Liquid Galaxy, the 15-foot range is too short to capture all types of engagement (some people look at it across the room), but from my experience with the system I think that users within this range could be accurately described as focused users—something worth measuring, but certainly not everything worth measuring. After noticing this, I retested condition 2 with my face about 5 feet from the DeepLens, after initially trying it from across a room.

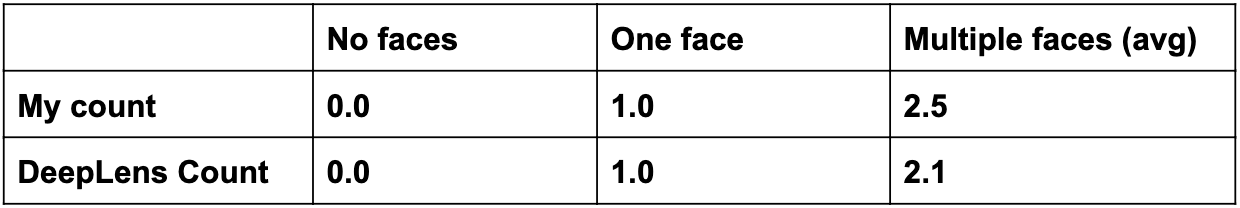

How did the DeepLens counts compare to my counts?

The model matched my performance in conditions 1 and 2, which makes a strong statement about its reliability in relatively static and close-up conditions such as looking at an empty room, or looking at someone stare at their laptop across a small table. In contrast, it did not count as many faces as I did in condition 3—so I’m happy to report I can still outperform A.I. on something.

Anyway, this suggests that the model is somewhat conservative, at least compared to my count (likely partly due to my eyes having a range larger than 15 feet). Therefore, when considering usage statistics gathered by a similar method, it might make most sense to think of the results as a lower bound, e.g. “the average number of people focused on the system was more than 2.1”.

It would be useful to experiment with the multiple faces condition again, to see how robust these findings are. It would also be helpful to keep track of factors like how much people move, the lighting, and the orientation of the camera, to see if they might impact the results. It would also be useful to automate the data collection and analysis.

This investigation has showed me that the DeepLens has a lot of potential as a tool for measuring engagement. Perhaps a future post will examine how it can be used to count users.

Thanks for reading! You are welcome to learn more about End Point Liquid Galaxy and AWS DeepLens.

machine-learning artificial-intelligence aws visionport serverless

Comments