Distributed Transactions and Two-Phase Commit

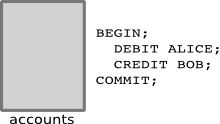

The typical example of a transaction involves Alice and Bob, and their bank. Alice pays Bob $100, and the bank needs to debit Alice and credit Bob. Easy enough, provided the server doesn’t crash. But what happens if the bank debits Alice, and then before crediting Bob, the server goes down? Or what if they credit Bob first, and then try to debit Alice only to find she doesn’t have enough funds? A transaction allows the debit and credit operations to happen as a package (“atomically” is the word commonly used), so either both operations happen or neither happens, even if the server crashes halfway through the transaction. That way the bank never credits Bob without debiting Alice, or vice versa.

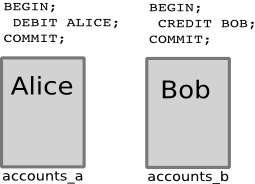

That’s simple enough, but the situation can become more complex. What if, for instance, for buzzword-compliance purposes, the bank has “sharded” its accounts database by splitting it in pieces and putting each piece on a different server (whether this is would be smart or not is outside the scope of this post). The typical transaction handles statements issued only for one database, so we can’t wrap the debit and credit operations within a single BEGIN/COMMIT if Alice’s account information lives on one server and Bob’s lives on another.

Enter “distributed transactions”. A distributed transaction allows applications to group multiple transaction-aware systems into a single transaction. These systems might be different databases, or they might include other systems such as message queues, in which case the transaction concept means a message would get delivered if and only if the rest of the transaction completed. So with a distributed transaction, the bank could debit Alice’s account in one database and credit Bob’s in another, atomically.

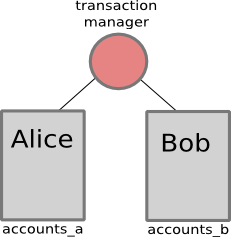

All this comes at some cost. Distributed transactions require a “transaction manager”, an application which handles the special semantics required to commit a distributed transaction. Second, the systems involved must support “two-phase commit” (which was added to PostgreSQL in version 8.1). Distributed transactions are committed using PREPARE TRANSACTION ‘foo’ (phase 1), and COMMIT PREPARED ‘foo’ or ROLLBACK PREPARED ‘foo’ (phase 2), rather than the usual COMMIT or ROLLBACK.

The beginning of a distributed transaction looks just like any other transaction: the application issues a BEGIN statement (optional in PostgreSQL), followed by normal SQL statements. When the transaction manager is instructed to commit, it runs the first commit phase by saying “PREPARE TRANSACTION ‘foo’” (where “foo” is some arbitrary identifier for this transaction) on each system involved in the distributed transaction. Each system does whatever it needs to do to determine whether or not this transaction can be committed and to make sure it can be committed even if the server crashes, and reports success or failure. If all systems succeed, the transaction manager follows up with “COMMIT PREPARED ‘foo’”, and if a system reports failure, the transaction manager can roll back all the other systems using either ROLLBACK (for those transactions it hasn’t yet prepared), or “ROLLBACK PREPARED ‘foo’”. Using two-phase commit is obviously slower than committing transactions on only one database, but sometimes the data integrity it provides justifies the extra cost.

In PostgreSQL, two-phase commit is supported provided max_prepared_transactions is nonzero. A PREPARE TRANSACTION statement persists the current transaction to disk, and dissociates it from the current session. That way it can survive even if the database goes down. The current session no longer has an active transaction. However, the prepared transaction acts like any other open transaction in that all locks held by the prepared transaction remain held, and VACUUM cannot reclaim storage from that transaction. So it’s not a good idea to leave prepared transactions open for a long time.

Distributed transactions are most common, it seems, in Java applications. Full J2EE application servers typically come with a transaction manager component. For my examples I’ll use an open source, standalone transaction manager, called Bitronix. I’m not particularly fond of using Java for simple scripts, though, so I’ve used JRuby for this demonstration code.

This script uses two databases, which I’ve called “athos” and “porthos”. Each has same schema, which provides a simple framework for the sharded bank example described above. This schema provides a table for account names, another for ledger information, and a simple trigger to raise an exception when a transaction would bring a person’s balance below $0. I’ll first populate athos with Alice’s account information. She gets $200 to start. Bob will go in the porthos database, with no initial balance.

5432 josh@athos# insert into accounts values ('Alice');

INSERT 0 1

5432 josh@athos*# insert into ledger values ('Alice', 200);

INSERT 0 1

5432 josh@athos*# commit;

COMMIT5432 josh@athos# \c porthos

You are now connected to database "porthos".

5432 josh@porthos# insert into accounts values ('Bob');

INSERT 0 1

5432 josh@porthos*# commit;

COMMIT

Use of Bitronix is pretty straightforward. After setting up a few constants for easier typing, I create a Bitronix data source for each PostgreSQL database. Here I have to use the PostgreSQL JDBC driver’s org.postgresql.xa.PGXADataSource class; “XA” is Java’s protocol for two-phase commit, and requires JDBC driver support. Here’s the code for setting up one data source; the other is just the same.

ds1 = PDS.new

ds1.set_class_name 'org.postgresql.xa.PGXADataSource'

ds1.set_unique_name 'pgsql1'

ds1.set_max_pool_size 3

ds1.get_driver_properties.set_property 'databaseName', 'athos'

ds1.get_driver_properties.set_property 'user', 'josh'

ds1.init

Then I simply get a connection from each data source, instantiate a Bitronix TransactionManager object, and begin a transaction.

c1 = ds1.get_connection

c2 = ds2.get_connection

btm = TxnSvc.get_transaction_manager

btm.begin

Within my transaction, I just use normal JDBC commands to debit Alice and credit Bob, after which I commit the transaction through the TransactionManager object. If this transaction fails, it raises an exception, which I can capture using Ruby’s begin/rescue exception handling, and roll back the transaction.

begin

s2 = c2.prepare_statement "INSERT INTO ledger VALUES ('Bob', 100)"

s2.execute_update

s2.close

s1 = c1.prepare_statement "INSERT INTO ledger VALUES ('Alice', -100)"

s1.execute_update

s1.close

btm.commit

puts "Successfully committed"

rescue

puts "Something bad happened: " + $!

btm.rollback

end

When I run this, Bitronix gives me a bunch of output, which I haven’t bothered to suppress, but among it all is the “Successfully committed” string I told it to print on success. Since Alice is debited $100 each time we run this, and she started with $200, we can run it twice before hitting errors. On the third time, we get this:

Something bad happened: org.postgresql.util.PSQLException: ERROR: Rejecting operation; account owner Alice’s balance would drop below 0

This is our trigger firing, to tell us that we can’t debit Alice any more. If I look in the two databases, I can see that everything worked as planned:

5432 josh@athos*# select get_balance('Alice');

get_balance

-------------

0

(1 row)

5432 josh@athos*# \c porthos

You are now connected to database "porthos".

5432 josh@porthos# select get_balance('Bob');

get_balance

-------------

200

(1 row)

Remember I’ve run my script three times, but Bob has only been credited $200, because that’s all Alice had to start with.

database open-source postgres ruby scalability

Comments