MDX

Recently I’ve been working with Mondrian, an open source MDX engine. MDX stands for “multi-dimensional expressions”, and is a query language used in analytical databases. In MDX, data are considered in “cubes” made up of “dimensions”, which are concepts analogous to “tables” and “columns”, respectively, in a relational database. And in MDX, much as in SQL, queries written in a special query language tell the MDX engine to return a data set by describing filters in terms of the various dimensions.

But MDX and SQL return data sets in very different ways. Whereas a SQL query will return individual rows (unless aggregate functions are used), MDX always aggregates rows. In MDX, dimensions aren’t simple fields that contain arbitrary values; they’re hierarchical objects that can be queried at different levels. And finally, in MDX only certain dimensions can be returned in a query. These dimensions are known as “Measures”.

Without an example this doubtless makes little sense at first glance. In my case, the underlying data come from a public health application. Among other responsibilities, public health departments have as their task to prevent the spread of disease. Some diseases, such as tuberculosis or swine flu, are of particular interest because of their virulence, their mortality, or other characteristics. Health care providers are legally required to report cases of these diseases to various public health organizations, where the data are analyzed to identify and control outbreaks. The cube in question describes cases of these reportable conditions. Dimensions include the particular disease, the patient’s gender and race, the health department jurisdiction the patient lives in, and a few other characteristics. Among the available measures are the count of cases, the average age of each patient, and the average duration of the local public health department’s investigation into the case.

You’ll note that each of the measures describes groups of cases: a count of cases, the average from a group of values, etc. MDX will tell me the number of cases that meet a criterion, for instance, but not the names of each patient involved. As I said before, MDX only returns aggregates, not individual rows. Each measure’s definition includes an aggregate function used to calculate the final value for that measure based on a group of rows in a database.

The cube also uses hierarchical dimensions. As an example, public health data categorizes cases by age group rather than by age. Groups include ‘< 1 year’ and ‘1-4 years’ at the young end, ‘85+ years’ at the older end, and five year increments for everything in between. So the age dimension hierarchy would include two levels: one for the age group, and one for the specific age. In some instances, the jurisdiction dimension might also be a hierarchy, with the public health department at the top level, and subdivisions such as county, zip code, or neighborhood in levels of increasing specificity underneath.

At this point, the SQL-oriented reader says, “Well, you can do all this in SQL,” and that is perfectly true. In fact, the major duty of an MDX engine is generally to translate MDX queries into SQL queries (or more often, sets thereof). The advantage of MDX is that sometimes it’s simply easier to express a particular set of dimensions and measures in MDX than in the corresponding set of SQL queries. Better still, there are nice applications that speak MDX and allow you to browse interactively through MDX cubes without knowing either MDX or SQL. And finally, when the data set gets really large, which is common in OLAP databases, the MDX engine knows about optimizations it can make to speed things up.

A simple MDX query might look like this:

SELECT

NON EMPTY {[Measures].[Quantity]} ON COLUMNS,

NON EMPTY

{([Markets].[All Markets], [Customers].[All Customers],

[Product].[All Products], [Time].[All Years],

[Order Status].[All Status Types])} ON ROWS

FROM [SteelWheelsSales]

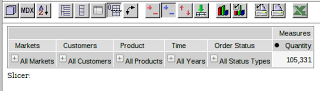

These data come from a cube that ships as a sample with the open source Pentaho business intelligence software suite. [SteelWheelsSales] represents the cube name; other bracketed expressions are measure and dimension names. “ON ROWS” and “ON COLUMNS” describe the “axis” on which the particular measure or dimensions should be displayed. The “ROWS” and “COLUMNS” axes exist by default, and others can be defined at will. The query above gives a result set like this one:

This image shows what a more complex Mondrian MDX session might look like. The cube describes sales data from a sample business. Users can easily “slice and dice” data to view trends over time, variations across sales regions or product lines, or mixtures thereof. In this case, the rows describe various combinations of dimension values, and each cell contains the one measure this query asks for, aggregated across the rows that match the corresponding dimensions.

For more on MDX query syntax or MDX in general, see this Microsoft library MDX reference.

database open-source pentaho reporting casepointer

Comments