How to Build a Skyscraper

Another talk from MountainWest RubyConf that I enjoyed was How to Build a Skyscraper by Ernie Miller. This talk was less technical and instead focused on teaching principles and ideas for software development by examining some of the history of skyscrapers.

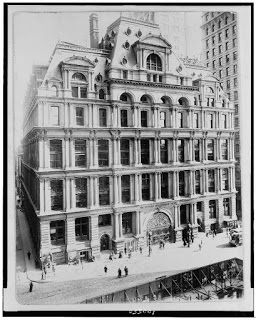

Equitable Life Building

Constructed from 1868 to 1870 and considered by some to be the first skyscraper, the Equitable Life Building was, at 130 feet, the tallest building in the world at the time. An interesting problem arose when designing it: it was too tall for stairs. If a lawyer’s office was on the seventh floor of the building, he wouldn’t want his clients to walk up six flights of stairs to meet with him.

Elevators and hoisting systems existed at the time, but they had one fatal flaw: there were no safety systems if the rope broke or was cut. While working on converting a sawmill to a bed frame factory, a man named Elisha Otis had the idea for a system to stop an elevator if its rope is cut. He and his sons designed the system and implemented it at the factory. At the time, he didn’t think much of the design, and didn’t patent it or try to sell it.

Otis’ invention became popular when he showcased it at the 1854 New York World’s Fair with a live demo. Otis stood in front of a large crowd on a platform and ordered the rope holding it to be cut. Instead of plummeting to the ground, the platform was caught by the safety system after falling only a few inches.

Having a way to safely and easily travel up and down many stories literally flipped the value propositions of skyscrapers upside down. Where lower floors were desired more because they were easy to access, higher floors are now more coveted, since they are easy to access but get the advantages that come with height, such as better air, light, and less noise. A solution that seems unremarkable to you might just change everything for others.

When the Equitable Life Building was first constructed, it was described as fireproof. Unfortunately, it didn’t work out quite that way. On January 9, 1912, the timekeeper for a cafe in the building started his day by lighting the gas in his office. Instead of disposing properly of the match, he distractedly threw it into the trashcan. Within 10 minutes, the entire office was engulfed in flame, which spread to the rest of the building, completely destroying it and killing six people.

Never underestimate the power of people to break what you build.

Home Insurance Building

The Home Insurance Building, constructed in 1884, was the first building to use a fireproof metal frame to bear the weight of the building, as opposed to using load-bearing masonry. The building was designed by William LeBaron Jenney, who was struck by inspiration when his wife placed a heavy book on top of a birdcage. From Wikipedia:

According to a popular story, one day he came home early and surprised his wife who was reading. She put her book down on top of a bird cage and ran to meet him. He strode across the room, lifted the book and dropped it back on the bird cage two or three times. Then, he exclaimed: “It works! It works! Don’t you see? If this little cage can hold this heavy book, why can’t an iron or steel cage be the framework for a whole building?”

With this idea, he was able to design and build the Home Insurance Building to be 10 stories and 138 feet tall while only weighing 1/3rd of what the same building in stone would weigh because he was able to Find inspiration from unexpected places.

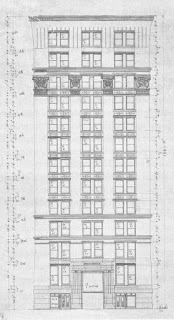

Monadnock Building

The Monadnock Building was designed by Daniel Burnham and John Wellborn Root. Burnham preferred simple and functional designs and was known for his stinginess while Root was more artistically inclined and known for his detailed ornamentation on building designs. Despite their philosophical differences, they were one of the world’s most successful architectural firms.

One of the initial sketches (shown) for the building included Ancient Egyptian-inspired ornamentation with slight flaring at the top. Burnham didn’t like the design, as illustrated in a letter he wrote to the property manager:

My notion is to have no projecting surfaces or indentations, but to have everything flush …. So tall and narrow a building must have some ornament in so conspicuous a situation … [but] projections mean dirt, nor do they add strength to the building … one great nuisance [is] the lodgment of pigeons and sparrows.

While Root was on vacation, Burnham worked to re-design the building to be straight up-and-down with no ornamentation. When Root returned, he initially objected to the design but eventually embraced it, declaring that the heavy lines of the Egyptian pyramids captured his imagination. We can learn a simple lesson from this: Learn to embrace constraints.

When construction was completed in 1891, the building was a total of 17 stories (including the attic) and 215 feet tall. At the time, it was the tallest commercial structure in the world. It is also the tallest load-bearing brick building constructed. In fact, to support the weight of the entire building, the walls at the bottom had to be six feet (1.8 m) wide.

Because of the soft soil of Chicago and the weight of the building, it was designed to settle 8 inches into the ground. By 1905, it had settled that much and several inches more, which led to the reconstruction of the first floor. By 1948, it had settled 20 inches, making the entrance a step down from the street. If you only focus on profitability, don’t be surprised when you start sinking.

Fuller Flatiron Building

The Flatiron building, constructed in 1902, was also designed by Daniel Burnham, although Root had died of pneumonia during the construction of the Monadnock building. The Flatiron building presented an interesting problem because it was to be built on an odd triangular plot of land. In fact, the building was only 6 and a half feet wide at the tip, which obviously wouldn’t work with the load-bearing masonry design of the Monadnock building.

So the building was constructed using a steel-frame structure that would keep the walls to a practical size and allow them to fully utilize the plot of land. The space you have to work with should influence how you build and you should choose the right materials for the job.

During construction of the Flatiron building, New York locals called it “Burnham’s Folly” and began to place bets on how far the debris would fall when a wind storm came and knocked it over. However, an engineer named Corydon Purdy had designed a steel bracing system that would protect the building from wind four times as strong as it would ever feel. During a 60-mph windstorm, tenants of the building claimed that they couldn’t feel the slightest vibration inside the building. This gives us another principle we can use: Testing makes it possible to be confident about what we build, even when others aren’t.

40 Wall Street v. Chrysler Building

The stories of 40 Wall Street and the Chrysler Building start with two architects, William Van Alen and H. Craig Severance. Van Alen and Severance established a partnership together in 1911 which became very successful. However, as time went on, their personal differences caused strain in the relationship and they separated on unfriendly terms in 1924. Soon after the partnership ended, they found themselves to be in competition with one another. Severance was commissioned to design 40 Wall Street while Van Alen would be designing the Chrysler Building.

The Chrysler Building was initially announced in March of 1929, planned to be built 808 feet tall. Just a month later, Severance was one-upping Van Alen by announcing his design for the building, coming in at 840 feet. By October, Van Alen announced that the steel work of the Chrysler Building was finished, putting it as the tallest building in the world, over 850 feet tall. Severance wasn’t particularly worried, as he already had plans in motion to build higher. Even after reports came in that the Chrysler Building had a 60-foot flagpole at the top, Severance made more changes for 40 Wall Street to be taller than the Chrysler Building. These plans were enough for the press to announce that 40 Wall Street had won the race to build highest since construction of the Chrysler Building was too far along to be built any higher.

Unfortunately for Severance, the 60-foot flagpole wasn’t a flagpole at all. Instead, it was part of an 185-foot steel spire which Van Alen had designed and had built and shipped to the construction site in secret. On October 23rd, 1929, the pieces of the spire were hoisted to the top of the building and installed in just 90 minutes. The spire was initially mistaken for a crane, and it wasn’t until 4 days after it was installed that the spire was recognized as a permanent part of the building, making it the tallest in the world. When all was said and done, 40 Wall Street was came in at 927 feet, with a cost of $13,000,000, while the Chrysler Building finished at 1,046 feet and cost $14,000,000.

There are two morals we can learn from this story: There is opportunity for great work in places nobody is looking and big buildings are expensive, but big egos are even more so.

Empire State Building

The Empire State Building was built in just 13 months, from March 17, 1930, to April 11, 1931. Its primary architects were Richmond Shreve and William Lamb, who were part of the team assembled by Severance to design 40 Wall Street. They were joined by Arthur Harmon to form Shreve, Lamb, & Harmon. Lamb’s partnership with Shreve was not unlike that of Van Alen and Severance or Burnham and Root. Lamb was more artistic in his architecture, but he was also pragmatic, using his time and design constraints to shape the design and characteristics of the building.

Lamb completed the building drawings in just two weeks, designing from the top down, which was a very unusual method. When designing the building, Lamb made sure that even when he was making concessions, using the building would be a pleasant experience for those who mattered. Lamb was able to complete the design so quickly because he reused previous work, specifically the Reynolds Building in Winston-Salem, NC, and the Carew Tower in Cincinnati, Ohio.

In November of 1929, Al Smith, who commissioned the building as head of Empire State, Inc., announced that the company had purchased land next to the plot where the construction would start, in order to build higher. Shreve, Lamb, and Harmon were opposed to this idea since it would force tenants of the top floors to switch elevators on the way up, and they were focused on making the experience as pleasant as possible.

John Raskob, one of the main people financing the building, wanted the building to be taller. While looking at a small model of the building, he reportedly said “What this building needs is a hat!” and proposed his idea of building a 200-foot mooring tower for a zeppelin at the top of the building, despite several problems such as high winds making the idea unfeasible. But Raskob felt that he had to build the tallest building in the world, despite all of the problems and the higher cost that a taller building would introduce because people can rationalize anything.

There are two more things we should note about the story of the Empire State building. First, despite the fact that it was designed top-to-bottom, it wasn’t built like that. No matter how a something is designed, it needs to be built from the bottom up. Second, the Empire State Building was a big accomplishment in architecture and construction, but at no small cost. Five people died during the construction of the building, and that may seem like a small number considering the scale of the project, but we should remember that no matter how important speed is, it’s not worth losing people over.

United Nations Headquarters

The United Nations Headquarters were constructed between 1948 and 1952. It wasn’t built to be particularly tall—less than half the height of the Empire State Building—but it came with its own set of problems. As you can see in the picture, the building had a lot of windows. The wide faces of the building are almost completely covered in windows. These windows offer great lighting and views, but when the sun shines on them, they generate a lot of heat, not unlike a greenhouse. Unless you’re building a greenhouse, you probably don’t want that. It doesn’t matter how pretty your building is if nobody wants to occupy it.

The solution to the problem was created years before by an engineer named Willis Carrier, who created an “Apparatus for Treating Air” (now called an air conditioner) to keep the paper in a printing press from being wrinkled. By creating this air conditioner, Carrier didn’t just make something cool. He made something cool that everyone can use. Without it, buildings like then UNHQ could never have been built.

Willis (or Sears) Tower

The Willis tower was built between 1970 and 1973. Fazlur Rahman Khan was hired as the structural engineer for the Willis Tower, which needed to be very tall in order to house all of the employees of Sears. A steel frame design wouldn’t work well in Chicago (also known as the Windy City) since they tend to bend and sway in heavy winds, which can cause discomfort for people on higher floors, even causing sea-sickness in some cases.

To solve the problem, Khan invented a “bundled tube structure”, which put the structure of a building on the outside as a thin tube. Using the tube structure not only allowed Khan to build a higher tower, but it also increased floor space and cost less per unit area. But these innovations only came because Khan realized that the higher you build, the windier it gets.

Taipei 101

Taipei 101 was constructed from 1999 to 2004 near the Pacific Ring of Fire, which is the most seismically active part of the world. Earthquakes present very different problems from the wind since they affect a building at its base, instead of the top. Because of the location of the building it needed to be able to withstand both typhoon-force winds (up to 130 mph) and extreme earthquakes, which meant that it had to be designed to be both structurally strong and flexible.

To accomplish this, the building was constructed with high-performance steel, 36 columns, and 8 “mega-columns” packed with concrete connected by outrigger trusses which acted similarly to rubber bands. During the construction of the building, Taipei was hit by a 6.8-magnitude earthquake which destroyed smaller buildings around the skyscraper, and even knocked cranes off of the incomplete building, but when the building was inspected it was found to have no structural damage. By being rigid where it has to be and flexible where it can afford to be, Taipei 101 is one of the most stable buildings ever constructed.

Of course, being flexible introduces the problem of discomfort for people in higher parts of the building. To solve this problem, Taipei 101 was built with a massive 728-ton (1,456,000 lb) tuned mass damper, which helps to offset the swaying of the building in strong winds. We can learn from this damper: When the winds pick up, it’s good to have someone (or something) at the top pulling for you.

Burj Khalifa

The newest and tallest building on our list, the Burj Khalifa was constructed from 2004 to 2009. With the Burj Khalifa, design problems came with incorporating adequate safety features. After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the problem of evacuation became more prominent in construction and design of skyscrapers. When it comes to an evacuation, stairs are basically the only way to go, and going down many flights of stairs can be as difficult as going up them—especially if the building is burning around you. The Burj Khalifa is nearly twice as tall as the old World Trade Center, and in the event of an emergency, walking down nearly half a mile of stairs won’t work out.

So how do the people in the Burj Khalifa get out in an emergency? Well, they don’t. Instead, the Burj Khalifa is designed with periodic safe rooms protected by reinforced concrete and fireproof sheeting that will protect people inside for up to two hours of during a fire. Each room has a dedicated supply of air, which is delivered through fire resistant pipes. These safe rooms are placed every 25 floors or so, because a safe space won’t do good if it can’t be reached.

You may know that the most common cause of death in a fire is actually smoke inhalation, not the fire itself. To deal with this, the Burj Khalifa has a network of high powered fans throughout which will blow clean air from outside into the building and keep the stairwells leading to the safe rooms clear of smoke. A very important part of this is pushing the smoke out of the way, eliminating the toxic elements.

It’s important to remember that these safe spaces, as useful as they may be, are not a substitute for rescue workers coming to aid the people trapped in the building. The safe rooms are only there to protect people who can’t help themselves until help can come. Because, after all, what we build is only important because of the people who use it.

Thanks to Ernie Miller for a great talk! The video is also available on YouTube.

Comments